Complex Carbohydrates & Glycemic Response

Informational facts about how carbohydrate structure affects blood glucose patterns and the body's metabolic response.

Carbohydrate Structure and Classification

Carbohydrates are organic compounds composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen arranged in various configurations. Monosaccharides (single sugar molecules: glucose, fructose, galactose) are the simplest units. Disaccharides (two sugar molecules: sucrose, lactose, maltose) consist of two monosaccharides joined by glycosidic bonds.

Polysaccharides are long chains of glucose molecules linked through glycosidic bonds. Starch (found in plants) and glycogen (stored in animals) both consist of glucose chains but differ in branch structure. Fibre—another polysaccharide—cannot be digested by human enzymes but serves important physiological functions through microbial fermentation and mechanical effects on the digestive system.

Digestion and Glucose Absorption

Carbohydrate digestion begins in the mouth with salivary amylase, which begins breaking starch into smaller polysaccharides. Pancreatic amylase continues this process in the small intestine, producing maltose (two glucose units) and other small oligosaccharides.

Intestinal enzymes (maltase, sucrase, lactase) then cleave these products into monosaccharides—primarily glucose. These individual glucose molecules are absorbed through the small intestine epithelium via specific transporters, then transported to the liver via the portal bloodstream.

Glycemic Response Factors

The rate at which glucose enters the bloodstream varies based on several factors: carbohydrate type, fibre content, food processing, meal composition (protein and fat content), and individual factors including insulin sensitivity and digestive capacity.

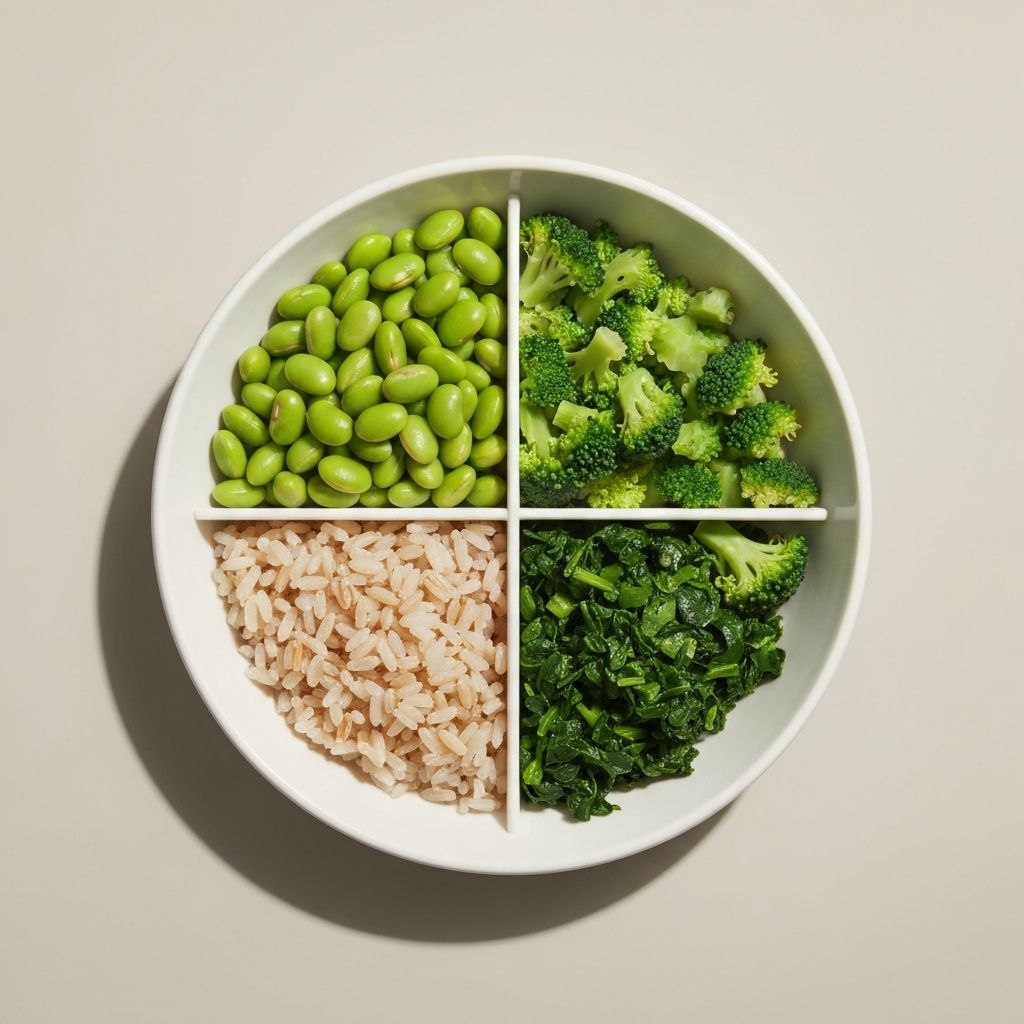

Whole grains retain their fibre and protein components, which slow glucose absorption and create more gradual blood glucose elevation. Refined grains have had these components removed, allowing faster glucose absorption and more rapid blood glucose increases. Individual responses to the same food vary substantially based on gut microbiota composition, physical fitness level, and metabolic characteristics.

Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Response

Rising blood glucose after carbohydrate ingestion stimulates pancreatic beta cells to secrete insulin. Insulin facilitates glucose uptake into muscle and adipose tissue, promotes glycogen synthesis in muscles and liver, and activates metabolic pathways that either store or oxidize glucose.

The magnitude of insulin secretion depends on several factors: the absolute glucose increase, the rate of glucose increase, and individual insulin sensitivity (the effectiveness with which tissues respond to insulin signals). Individuals with greater insulin sensitivity typically show smaller insulin responses to the same glucose stimulus, while those with insulin resistance require larger insulin secretion to achieve the same glucose-lowering effect.

Glycogen Storage and Utilization

Excess glucose beyond immediate energy needs is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles. The liver maintains a glycogen store of approximately 100-120 grams, while muscle glycogen stores typically contain 400-600 grams depending on muscle mass and training status. These glycogen pools serve different functions.

Hepatic glycogen is released during fasting states to maintain blood glucose for the brain and other glucose-dependent tissues. Muscle glycogen is available only to the muscle cell where it is stored, supporting that muscle's contraction during physical activity. Glycogen can be rapidly mobilized—each glucose unit can be released within minutes—making it an efficient short-term energy reserve.

Fibre and Carbohydrate Metabolism

Dietary fibre—indigestible carbohydrates—cannot be broken down by human enzymes but undergoes partial fermentation by gut microorganisms. Different fibre types are fermented at different rates, producing short-chain fatty acids (butyrate, propionate, acetate) that are absorbed and used for energy and cell signalling.

Physiological Effects of Fibre

- Slows glucose absorption, modulating blood glucose response

- Increases intestinal transit time, extending nutrient absorption window

- Provides substrate for beneficial gut bacteria fermentation

- Contributes bulk to intestinal contents, affecting mechanoreceptor signalling

- Influences hormone-producing cells' nutrient exposure patterns

The type and amount of fibre in carbohydrate sources substantially influences metabolic response. Whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits contain different fibre types that produce distinct metabolic effects.

Individual Variation in Carbohydrate Response

Identical carbohydrate foods produce different glucose responses in different individuals—sometimes as much as three-fold variation. This variation reflects differences in: insulin secretion patterns, insulin sensitivity, gut microbiota composition, digestive enzyme activity, and physical fitness level.

Additionally, the same individual shows variable glucose responses to identical foods on different occasions, depending on sleep quality, stress level, time of day, physical activity patterns, and recent dietary intake. This dynamic variation demonstrates that glucose homeostasis reflects complex integration of multiple regulatory systems rather than a simple input-output relationship.

Educational Information Only

This article provides scientific explanation of carbohydrate metabolism for educational purposes. It does not provide dietary recommendations regarding carbohydrate types or quantities. Individual carbohydrate requirements and optimal sources vary based on metabolic status, activity level, health conditions, and personal preferences. For personalised nutritional guidance, consult registered dietitians or healthcare professionals.